Stewardship in wildlife tourism: Lessons learned and insight for future practice

The ongoing impact of the Anthropocene calls for humans to reconsider their interactions with the natural environment and engage in a more sustainable model of tourism, including ‘wildlife tourism’ (Thomsen et al., 2021).

Wildlife tourism includes hunting, fishing, as well as passive (e.g., distant observation) and active (e.g., feeding, touching and swimming) interactions with animals (Dou & Day, 2020). This area of tourism has grown over the past decade and now comprises up to 40% of tourism worldwide, providing opportunities in employment and regional development (Thomsen et al., 2021). Wildlife tourism is well positioned to capture social attention and economic resources, which could be channelled into restoring and protecting ecosystems (D’cruze et al., 2017). However, to ensure practice that is consistent with the principles of sustainable development, wildlife tourism must encompass education and community development to conserve the natural environment and the communities that surround it (Liburd & Becken, 2017; Thomsen et al., 2021).

To redress the potential impact of this form of tourism, participating individuals (herein tourists) should be encouraged to adopt “an ethic of care” (Walker & Weiler, 2017, p.272). These practices require personal reflection, which involves connecting the experience to tourists’ personal lives to create a response with the intent of adapting more pro-environmental behaviours (Walker & Moscardo, 2014). As part of their personal reflection, tourists are encouraged to adopt a transformative approach, which means understanding why one is engaging in the experience and what they are hoping to transform, for example, changing their behaviour and engaging in more sustainable practices (Vidickienė et al.,2021).

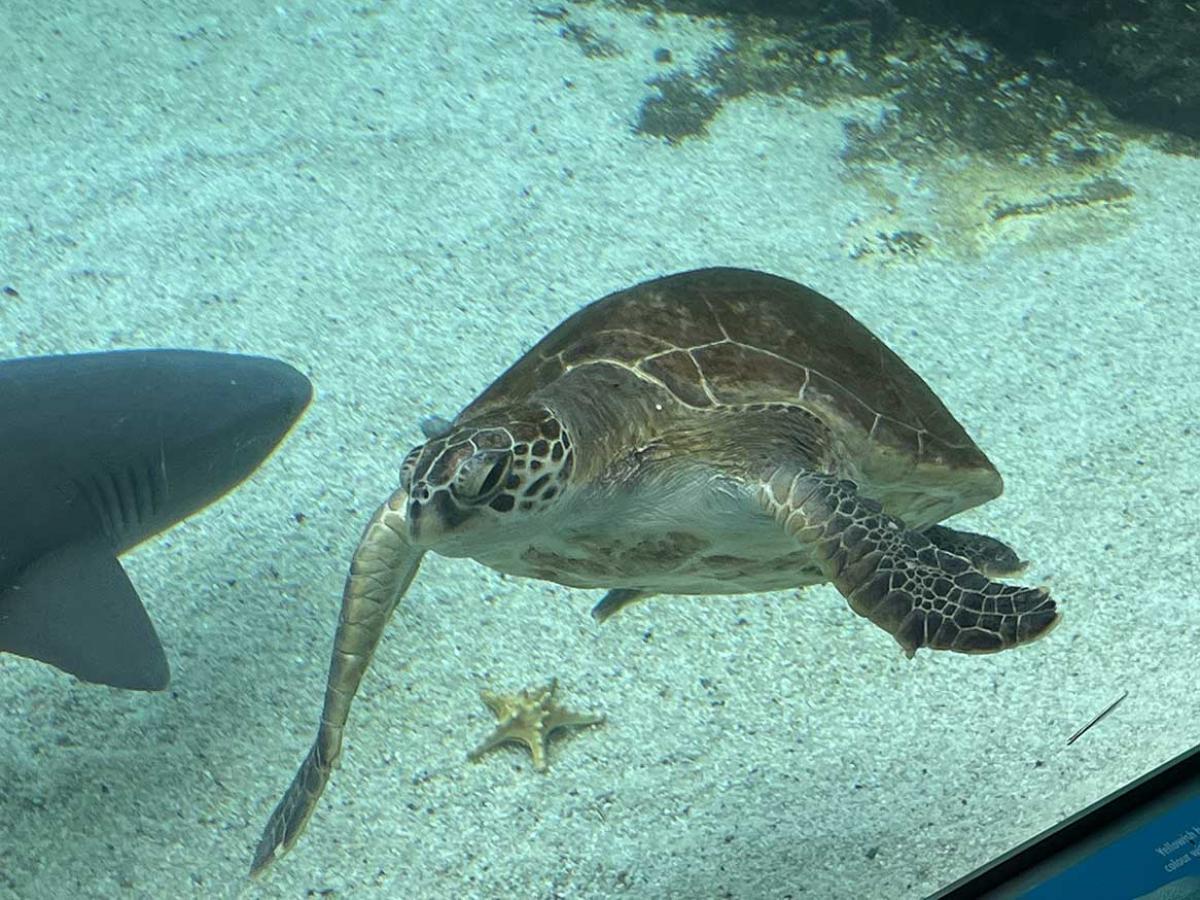

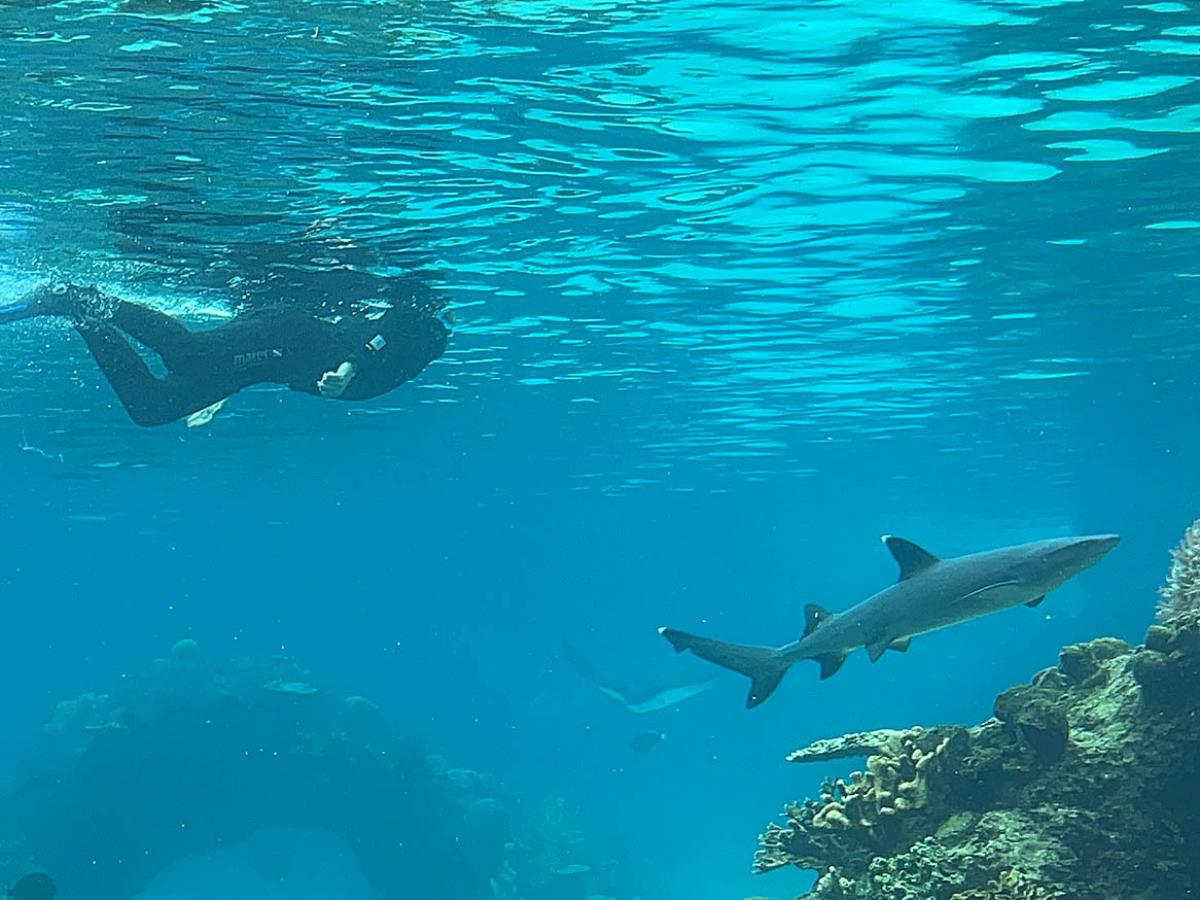

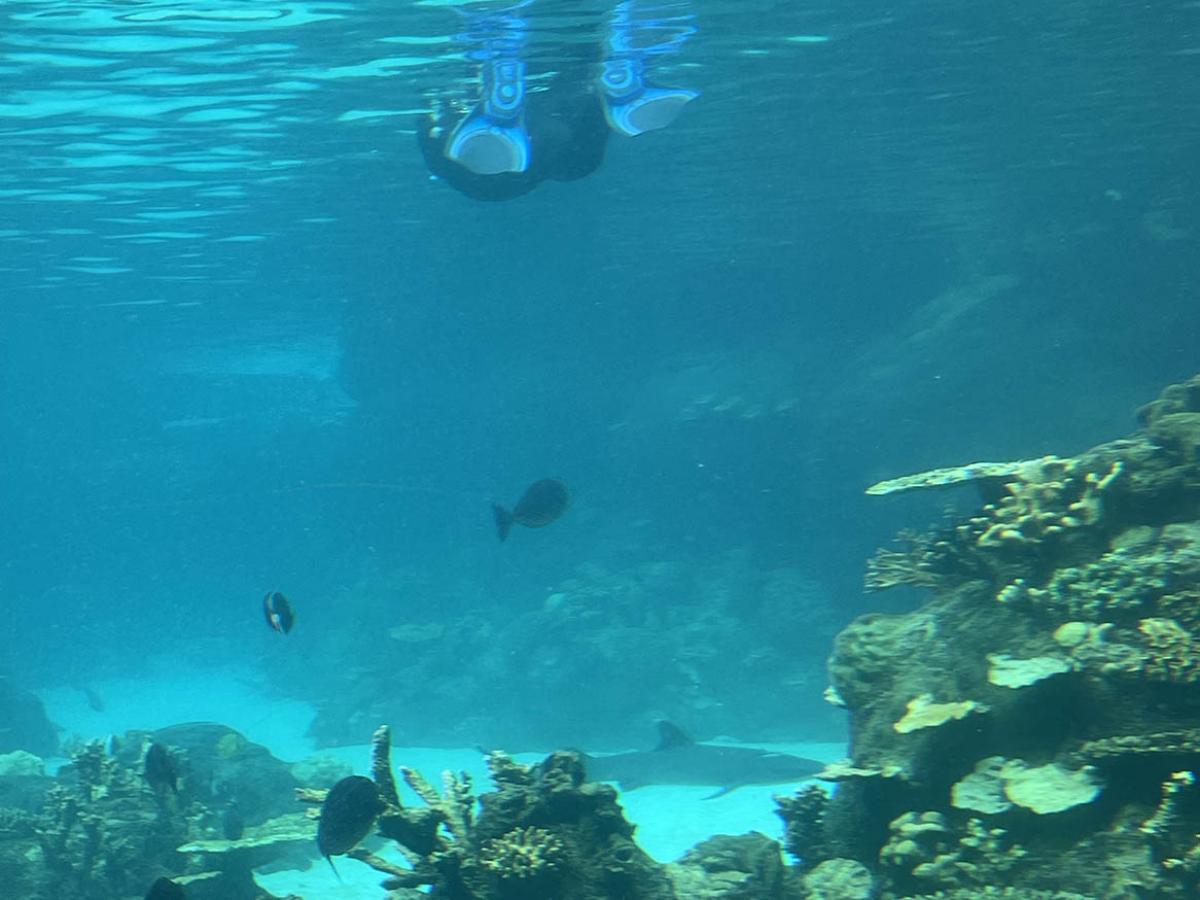

Tourist guides can foster these interpretive practices by reflecting on their knowledge, values and objectives within their role and applying this to the tourist’s experience (Walker & Weiler 2017). For example, Sea World’s Reef Snorkel in the Australian state of Queensland allows tourists to snorkel with marine wildlife such as tropical fish, stingrays and Bull sharks, whilst educating guests about the conservation of wildlife (Sea World 2022). Sea World, including their Research and Rescue Foundation, are a member of the Zoo Aquarium Association Australasia, which accredits organisations based on their contributions to the conservation and welfare of animals, using an internationally renowned assessment known as the Five Domains Model (Sea World, 2022; Zoo and Aquarium Association, 2022).

Wildlife tourism should also engage the community through education (Thomsen et al., 2021). One of the ways this can be achieved is through employing local guides who have a vast knowledge of native flora and fauna (D’cruze et al., 2017). The benefit of this is that locals can use their personal experiences to enhance the interpretive aspect of education and create meaningful engagement for tourists as well as improve local conservation efforts (Lee, Jan & Chen, 2021; Thomsen et al., 2021).

Education can also be used to engage broader community respect and care for the natural environment. For example, in Whyalla, South Australia, frequent tourist interactions with local pods of dolphins have prompted the Eyre Peninsula Landscape Board to introduce signage along the marina. The aim of this initiative is to prevent locals and tourists from feeding and touching the dolphins by educating them on the dangers of engaging in this behaviour (Hamilton & Leckie, 2020).

South Australia’s new Tourism Minister, the Hon. Zoe Bettison MP has recently shared her aspirations for the State to continue work in this direction, highlighting that tourism represents a significant opportunity for the state to reverse the impacts of COVID-19 and build a sustainable future. The State Government is investing significantly to this end and plans to provide $1.6 million to build the industry’s capability and encourage more young people to consider a career in tourism.

Wildlife tourism operators taking advantage of this investment should prioritise education with an emphasis on interpretive practices (Thomsen et al., 2021), using the knowledge of local communities to create opportunities for community development and conservation efforts (D’cruze et al., 2017), and employ local guides who are passionate, engaging and can encourage tourists to actively reflect on their behaviour (Walker & Moscardo, 2014).

Authors

Dr Tracey Dodd and Ms Grace Pihir

References

D'cruze, N., Machado, F. C., Matthews, N., Balaskas, M., Carder, G., Richardson, V., & Vieto, R. (2017). A review of wildlife eco-tourism in Manaus, Brazil. Nature Conservation, 22, 1-16.

Dou, X., & Day, J. (2020). Human-wildlife interactions for tourism: a systematic review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(5), 529-547.

Hamilton, J & Leckie E. (2020). ‘Whyalla dolphins feeding warnings draw mixed from SA fishers’, ABC Eyre Peninsula, 3 August, viewed 4 May 2022 (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-03/whyalla-illegal-dolphins-feeding…)

Lee, T. H., Jan, F. H., & Chen, J. C. (2021). Influence analysis of interpretation services on eco-tourism behavior for wildlife tourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, published online ahead of print,,1-19, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1949016.

Liburd, J. J., & Becken, S. (2017). Values in nature conservation, tourism and UNESCO World Heritage Site stewardship. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(12), 1719-1735.

Sea World. (2022), Tropical Reef Snorkel, Sea World, viewed 9 May 2022 (https://seaworld.com.au/attractions/animal-adventures/tropical-reef-sno…)

Thomsen, B., Thomsen, J., Copeland, K., Coose, S., Arnold, E., Bryan, H., ... & Chalich, G. (2021). Multispecies livelihoods: a posthumanist approach to wildlife eco-tourism that promotes animal ethics. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1-19.

Vidickienė, D., Gedminaite-Raudone, Z., Vilke, R., Chmielinski, P., & Zobena, A. (2021). Barriers to Start and Develop Transformative Ecotourism Business. European Countryside, 13(4), 734-749.

Walker, K., & Moscardo, G. (2014). Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: eco-tourism, interpretation and values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(8), 1175-1196.

Walker, K., & Weiler, B. (2017). A new model for guide training and transformative outcomes: a case study in sustainable marine-wildlife eco-tourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 16(3), 269-290.

Zoo and Aquarium Association. (2022), About the Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA), Zoo and Aquarium Association, viewed 9 May 2022 (https://www.zooaquarium.org.au/public/Public/About/About.aspx?hkey=c739…)

Study

We offer a range of business related degrees, enabling students to choose their own path and become career ready.